It’s crazy I’m thinking, just knowing that the world is round.

I’m here I’m dancing on the ground.

Am I right side up or upside down?

– Dave Matthews Band

This post addresses the perennial question: “Why do we cut the pavilion first?”

I’m never comfortable with the answers I see floated for this, so I’m going to weigh-in on it in some depth. First, let’s debunk some myths:

Myth #1: “Cutting the pavilion first is just better.” isn’t really any sort of explanation. And, it has the structure of dogma.

Myth #2: “Cutting the pavilion first allows gathering maximum weight in the pavilion, and crown angles can just be shifted at will later.”

There are two claims, here:

A. Pavilion-first cutting preserves more weight.

B. Crown angles are unimportant to gem appearance.

We can debunk claim A pretty quickly by comparing weight yield of a preponderance of pavilion-first-cut gems against the weight yield of a preponderance of crown-first-cut gems. And, “native-style”, crown-first strategy easily and consistently wins.

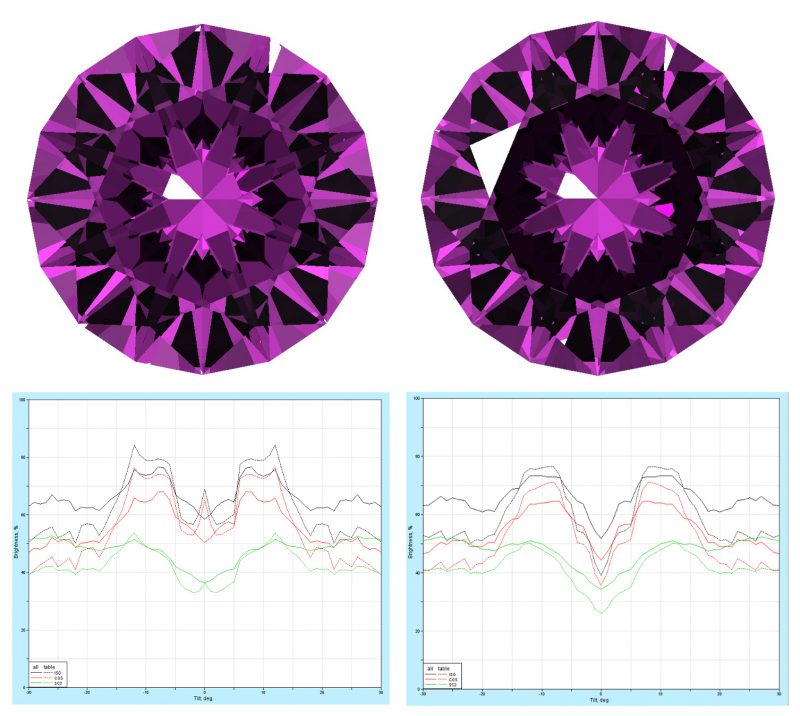

We can debunk claim B by doing just a bit of ray-tracing, or even test-cutting, if one is inclined toward harder proof:

The left half of the image above shows a Long&Steele SRB rendered at RI=1.76 (corundum). The right half of the image is a rendering of the same design, the only difference being crown angles lowered by just TWO degrees. The black-eye rendering on the right is about as dramatic as the light-return graph below it.

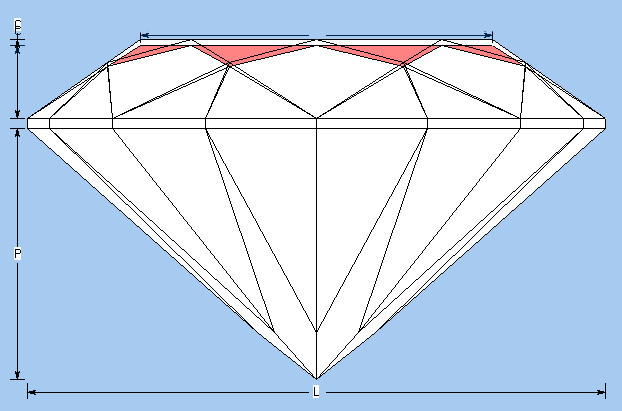

Depending on the design, you don’t have to lower the crown angles by much to ruin the appearance of the finished gem. This image shows a side-view of the original angles superimposed on the minus-two-degree crown. I’ve highlighted the star facets of the lowered crown in pink to make them more visible.

To further make the point, in this image, compare the distance we’ve lowered the table – with the thickness of the girdle…

So, obviously, choosing to cut the pavilion first because we think that’s going to allow us to play games with the crown height “to maximize yield” – isn’t really a strategy.

Myth #3: “If we cut the crown first, the pavilion will necessarily have poor geometry (causing window, extinction, etc)”. The popularity of myth makes me wonder how anyone ever repairs a chipped culet without completely re-cutting a gemstone. (Not knowing how to do something isn’t the same thing as it being impossible.)

“Where should I go?” – Alice.

“That depends on where you want to end up.” – Cheshire Cat.

Methods and techniques should serve outcomes rather than dictating them.

We can use a center-point angle method to create a precise girdle plan on which a precise crown plan will easily fit.

While that’s an easier way for less-practiced hands to cut – or for any hands to produce a highly-complex and precise gem, this does not mean it’s the only way (or even the most advantageous way) to cut every single stone:

The quality and presentation of color comprises 60% (or more) of the value in a colored stone. Thus, we must prioritize each feature of the gem with regard to its influence on the final appearance and value of the finished piece.

Cutting means adjusting the boundaries of a gemstone (boundaries become facets on the finished gem). The boundaries are adjusted relative to inherent physical features of the rough stone, such as:

- Color direction & zoning

- Gross shape of stone

- Flaws and inclusions in the stone

In a faceted stone, each boundary (facet) may be either a window through which we can peer into the stone – or a mirror reflecting light and features back to our eye – or in some cases, both.

So, we will always use the most careful and precise pre-forming process. And, there may also be times when we choose to alter the cutting process (usual order of operations) to improve our control over specific features.

Things that may lead us to alter our process include the proximity of a feature to a boundary, the precision required for placing the feature, or the priority of that placement relative to other considerations.

Which and when: Pavilion First

We can use CAM or OMNI methods to create precise preforms and sophisticated designs.

We can precisely place pavilion location and optical geometry to manipulate presentation of color and inclusions:

We can use equipment that lets us do this with lower manual skills than necessary for competent-grade “primitive cutting”.

Because color accounts for between 50% and 70% of a gem’s value, presentation of color can at times, be more important than gross weight. The pavilion is the part of the gem with greatest influence over color presentation – such as how one orients color zoning, or places the more-saturated areas of a gem, or orients optics to directional color. Selection of design features can also dramatically affect color saturation and tone – and therefore, value.

Part of what influences “pavilion-first” strategy is the understanding that “weight is fine, but color is final” – in terms of desirability of a given gemstone.

Which and when: Crown First

We can complete the largest and most difficult facet first.

We can create a window into the stone to see color zoning, flaws, and inclusions before doing any other work. For instance, if we’re especially concerned about an inclusion in the crown area, rather than estimating in an imprecise way, we may choose to cut the table and crown to carefully remove (or include) the inclusion in the most exacting way – and then construct the pavilion beneath it.

When the pavilion is cut last, it’s tailored to the girdle plan, and the geometry of the pavilion is often more concerned about preservation of weight than optics. However, in designs like the classic Ceylon cut, the angles of the pavilion facets are usually quite forgiving, though when it’s taken to extremes just to preserve weight we’ll get a finished stone with a “fat” rounded pavilion (sometimes very lopsided), and usually a bad window.

Outcome-driven Strategies

Using modern faceting equipment, we can most often manage color and inclusion most powerfully – and produce the most interesting finished pieces – with processes that begin in the pavilion and progress to the crown.

However, there are exceptions – and very important ones. The most notable ones involve critical or unusual color zoning, flaws, or inclusions.

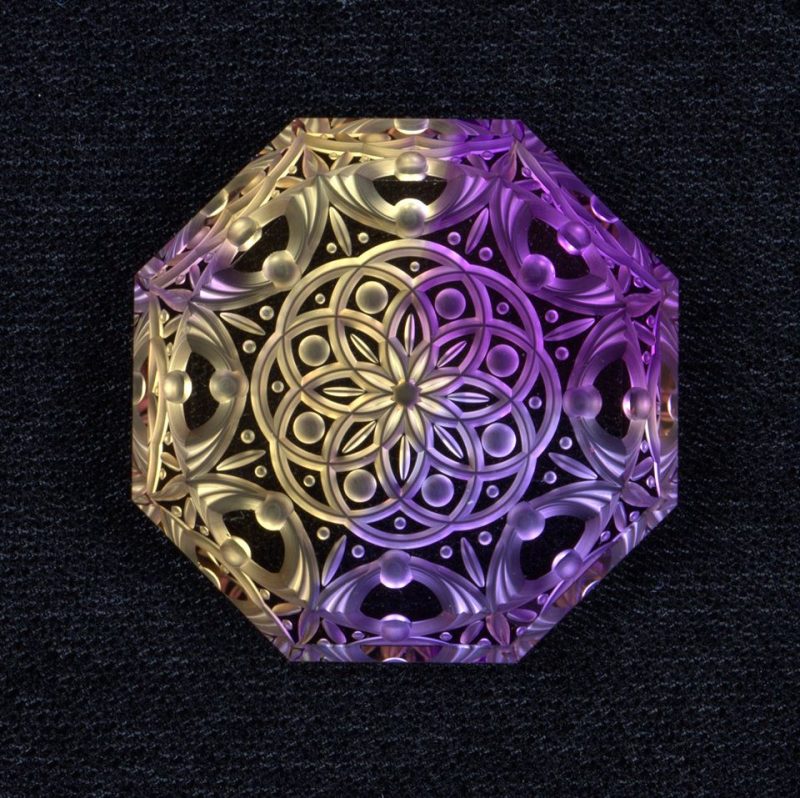

Also, newer cutting methods that involve mixed cuts, concave work, and especially the fantasy style work being pioneered by Dalan Hargraves – is likely to offer more circumstances where we will want to consider cutting the crown first.